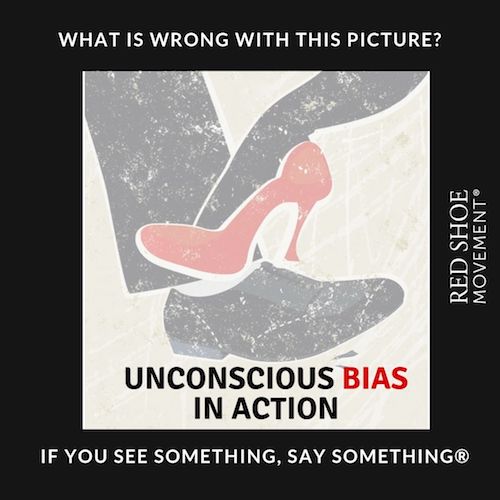

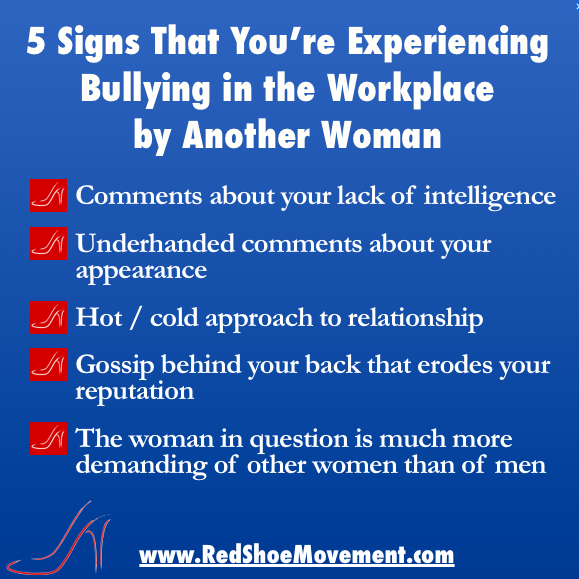

How does discrimination in the workplace manifest itself and what can you do to change any subconscious discrimination that may be at play?

Revealing new research from Catalyst and insightful analysis by our very own, Mariela Dabbah.

By Mariela Dabbah

The latest flurry of women being named to high positions is welcome news.

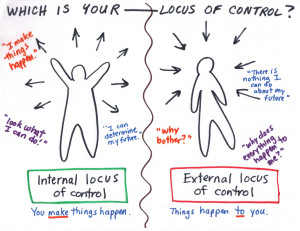

In the last few months we’ve seen Janet Yellen become chairwoman of the Federal Reserve, Mary Barra take the helm as the first female CEO of GM, and Melissa Mark-Viverito step in as Speaker of the New York City Council. Unfortunately, this great news has a seldom-discussed downside. It creates the illusion that there’s no longer need for companies and organizations to make an effort to address discrimination in the workplace. That opportunities to rise to the top jobs are available to everyone regardless of gender or background. That you only need to want the job badly enough to get it.

Is discrimination in the workplace unavoidable?

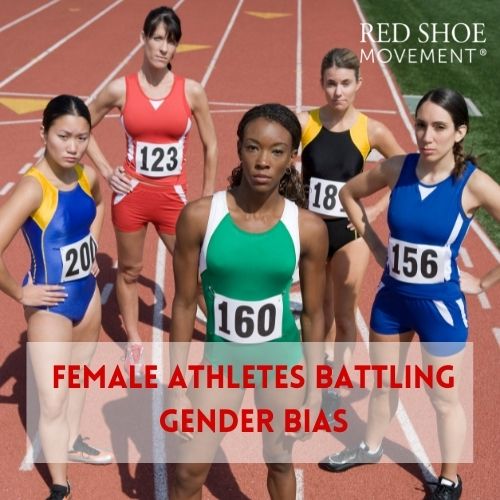

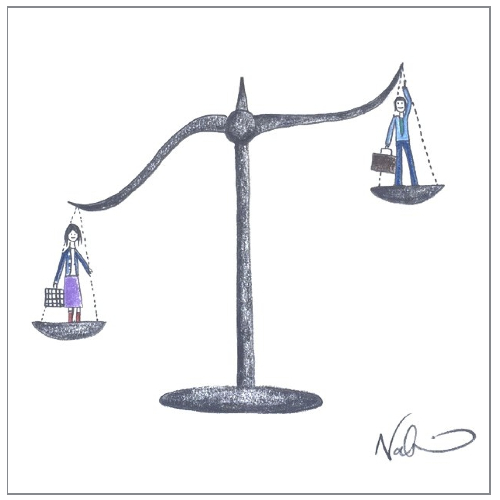

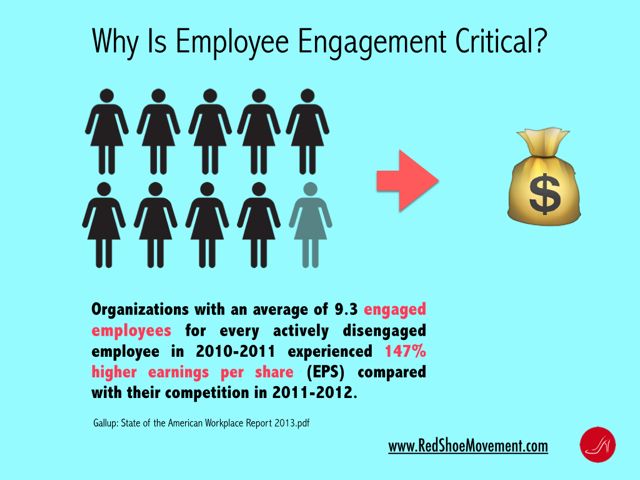

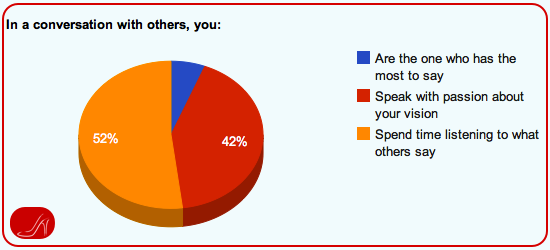

A recent study by Catalyst confirmed that feeling like the “other” at work eventually impacts an individual’s behavior. It begins with a real lack of access for people who feel racially/ethnically different. For example, people who feel different than others at work are assigned less senior-level mentors than those who don’t feel different. (58% of women who felt racially/ethnically different had mentors who were CEO’s or senior executives, as compared to 71% of women and 77% of men who didn’t feel different.) Chances to get plum assignments diminish when someone lacks senior-level mentors who can offer opportunities, and the likelihood of career advancement decreases as well. Over time, people who feel different than their work colleagues start downsizing their career aspirations. In general, women are more likely than men to downsize their aspirations (35% compared to 21%), but this difference is even larger for women who feel racially/ethnically different (46%) and even more pronounced for those with multiple dimensions of “otherness,” (for example, a Hispanic woman.) In addition, being a mother resulted in the downsizing of career aspirations being even more pronounced.

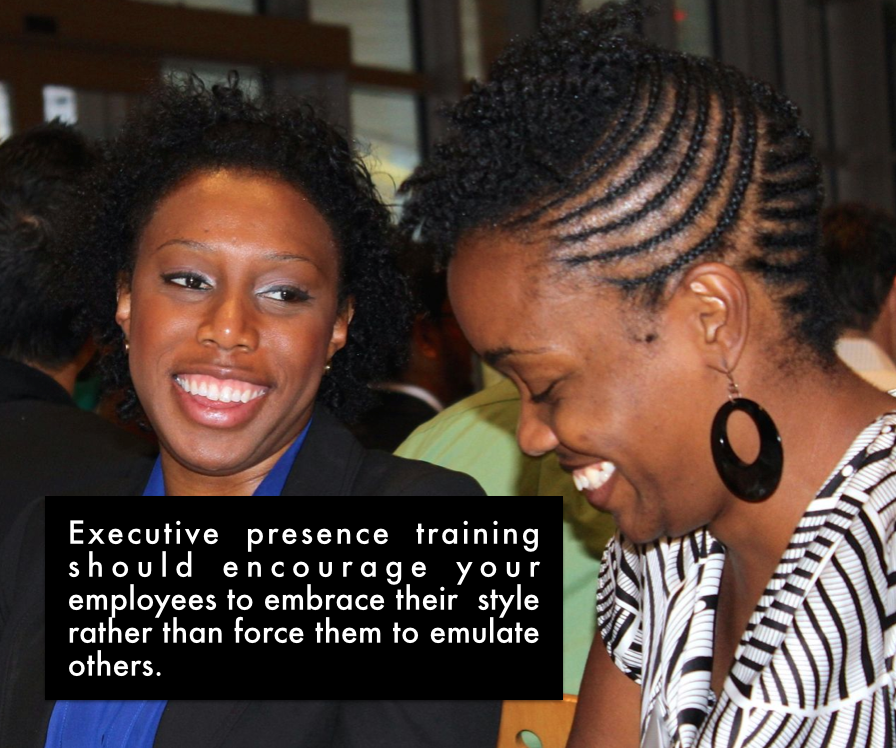

So what might be interpreted as self-discrimination in the workplace due to a lack of knowledge of what’s needed to move ahead (seek senior-level mentors who can become sponsors, for example) is in reality something different. Catalyst’s report concludes that fewer opportunities for those with multiple dimensions of “otherness” may be what’s harming their aspirations. In other words, an organization’s lack of mechanisms and strategies to guarantee that every high potential has equal access to a successful career track is what’s failing, not the lack of employees’ aspirations.

Not surprisingly, the report showed that women who felt racially/ethnically different were least likely to be at senior executive or CEO level in their organizations (10%, compared with 16% of women who didn’t feel different.)

What can you do to change any subconscious discrimination in the workplace that may be at play?

As someone looking for change, whether an HR practitioner or a professional woman feeling the impact of this reality, there are several things you can do.

1. Start by asking questions:

How are mentors matched with high potentials?

How can your company ensure access to high-level sponsors for all high potentials?

Are your ERGs leveling the playing field for people who feel as “others” or are they unknowingly perpetuating discrimination in the workplace?

Are there effective metrics in place to track the progress of all high potentials, including those with multiple dimensions of diversity?

2. Print Catalyst’s report and bring it to work. Compare your numbers with those in the study. Organize rounds of candid conversations with all stakeholders to review and change any policies that negatively impact the career opportunities of your talent.

3. Implement an experiential program where those in the majority get to feel “other” for a little while. Nothing like a personal experience to change people. For example, if you’re in a white male dominant company, send groups of two or three men to different multicultural women’s conferences. Or if the majority speaks English only, sit them in front of a Spanish comedy for an hour surrounded by Spanish speakers without the chance to change the channel.

These findings are not new. We’ve been discussing for decades the fact that people with diverse backgrounds (women more than men) have a harder time moving up the career ladder than their Anglo Saxon counterparts. This report gives us all reason to do our part to shake things up right now. Let’s not stay on the sidelines. Let’s take center stage and get it done.